The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season could shape up to be one of the most active on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The agency has released its annual hurricane forecast—and NOAA Administrator Rick Spinrad said in a press conference that the number of storms predicted to form this year is “the highest NOAA has ever issued.”

The agency is forecasting a total of 17 to 25 named storms in the 2024 season, which begins on June 1 and ends November 30. As many as 13 of those storms are likely to develop into hurricanes—and four to seven could become major hurricanes, which is defined as category 3 or higher. Overall, NOAA forecasters predict an 85 percent chance of an above-average hurricane season.

“This season is looking to be an extraordinary one in a number of ways,” Spinrad said.

The announcement is likely no surprise to experts who have been monitoring conditions. Experts who spoke with National Geographic in March warned that warm sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean and the development of a La Niña in the Pacific may create a “perfect storm” of the conditions needed for major hurricanes.

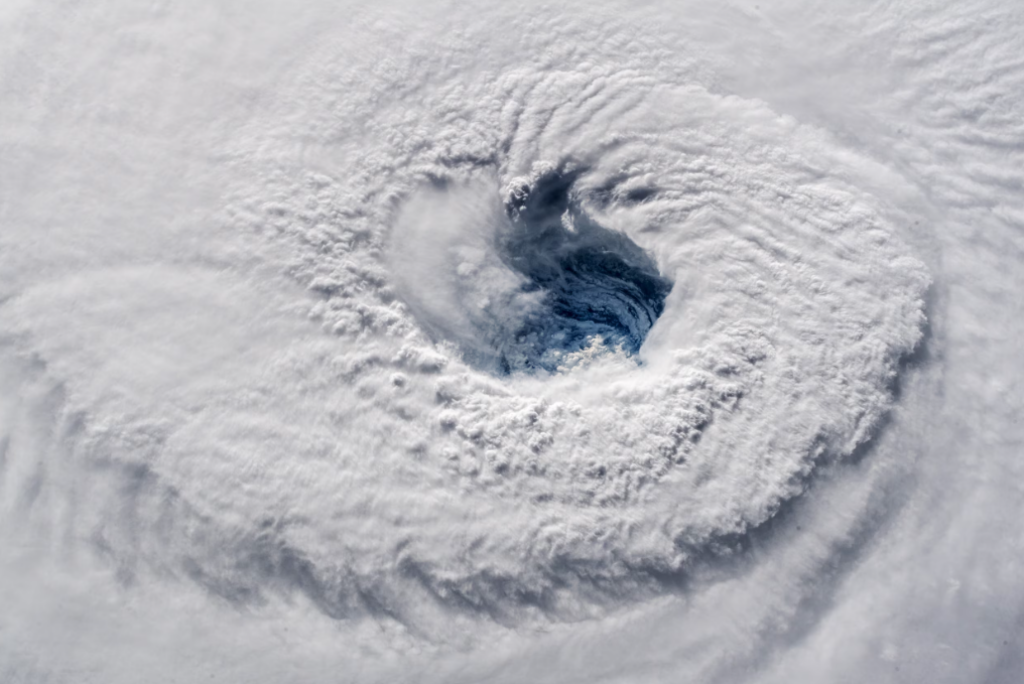

How hurricanes form

Key to the formation of any tropical cyclone—known variously as hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones depending on their location—is the combination of warm ocean temperatures and the absence of what is known as wind shear.

Alex DaSilva, lead hurricane forecaster with AccuWeather, explains that wind shear occurs when wind changes direction and speed at different heights in the atmosphere. Wind shear prevents tropical cyclones, he says, by essentially knocking over storm clouds to prevent them from rising straight up into the atmosphere. “And so that kind of prevents typically tropical systems from really intensifying.”

Tropical storms also need surface water to be at a temperature of 79 degrees Fahrenheit (26 Celsius) or higher. That warm water, and the warm air just above it, provides fuel for the storm; as warm air rushes upward, it creates a low-pressure system beneath the hurricane, into which more warm air rushes, allowing the storm to keep growing.

The intensity of an individual storm owes more, however, to the heat content of the ocean’s top 330 feet or so, explains Matt Rosencrans of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

“If that water is very shallow, you’ll stir that all up and maybe pull up some cold water. But if you have a large reservoir of warm water, the storm will keep pulling the water,” he says.

Record warm waters

Officially, hurricane season begins June 1 and runs through November, with storms at their most intense and numerous from August into October. One reason why some forecasters are anticipating an active season is that sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic were at record highs as early as February.

“Sea surface temperatures in what we call the main development region of the Atlantic…., off the coast of Africa to off the coast of Central America, are 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 F) above normal,” says Rosencrans. “That’s a record value for February.”

That means that, if those waters continue to warm at the usual rate as the year progresses, there will be plenty of fuel from which any potential storms can draw.

Meanwhile, another significant potential factor in this year’s hurricane season is taking shape thousands of miles away in the Pacific.

How La Niña affects hurricanes

Over periods ranging from three to seven years, the waters of the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean alternately warm and cool as a result of a recurring climate pattern called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). During an El Niño, sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific increase, and those warmer temperatures affect the path of the Pacific jet stream, which in turn brings drier, warmer weather to the northern United States and Canada, and wetter conditions to the Gulf Coast and southeast.

El Niño also makes Atlantic hurricanes less likely to form because it generates more wind shear and suppresses hurricane activity.

La Niña has the opposite effect, reducing wind shear, and aiding the formation of hurricanes.

During the 2023 season, ENSO was in an El Niño phase. Changes in water temperature and other clues suggest strongly that, by the time the 2024 season starts, it will have transitioned into a “neutral” phase, but that by the peak months, it is likely to have shifted fully into a La Niña.

“How quickly that transition occurs can affect everything as well,” says DaSilva. “There’s a lag time, so it can take a month or two for the full effects of the pattern to settle in. So, while we expect the transition to occur in mid-summer, it may not be until late summer or fall where we really see those effects across the Atlantic basin.”

As a result, he says, this year’s hurricane season could remain particularly active deep into November.

As for what exactly an active season would entail: while early for any predictions, DaSilva notes that an average season sees 14 named tropical storms in the Atlantic, with seven reaching hurricane category; last year, when waters were warm in the Atlantic but an active El Niño provided unfavorable wind shear conditions, there were 20 storms and seven hurricanes.

Of course, no long-range forecast can predict when individual storms will arise or the paths they will take, but DaSilva cautions that those who live in areas prone to hurricanes, especially around the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, should prepare.

“If a tropical storm system comes into this area, it could rapidly intensify, potentially close to land,” he cautions. “And that’s why people need to be on alert and have their hurricane plans ready. Because any system with these kinds of conditions can explode very quickly. That’s what we’re concerned about.”